A Forest of Actors

by Neil C Smith

The recent release of PraxisLIVE v4 saw a focus on relicensing the PraxisCORE runtime, and promoting its standalone usage as a platform for media processing, data visualisation, sensors, robotics, IoT, and lots more. PraxisCORE is a modular runtime for cyberphysical programming, supporting the real-time coding of real-time systems. Absolutely essential to this is its asynchronous, shared-nothing message-passing system - a forest-of-actors evolution of the standard actor model with the needs of real-time processing in mind.

What’s the problem?

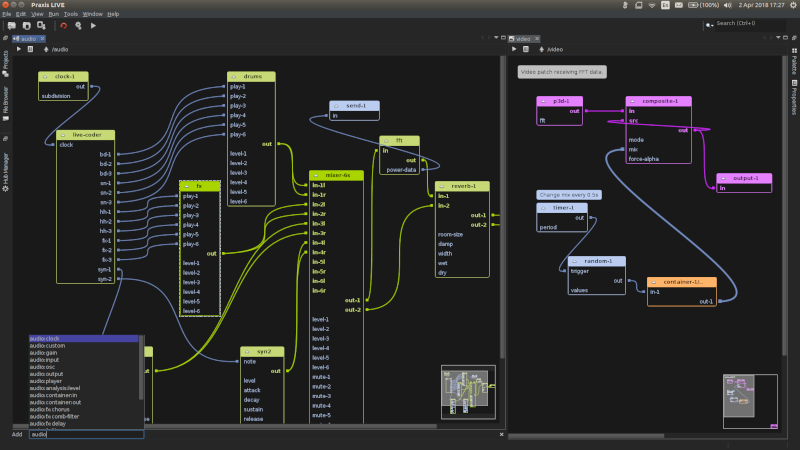

While the PraxisCORE architecture can be used for processing any type of data, it was initially designed with the needs for working with multiple real-time media streams in mind. For example, my creative work often involves working with audio and video together, or a low frame-rate camera doing motion detection and controlling a high frame-rate projection. Sometimes you might be working with video working at 60 fps and audio processing at 750 fps (PraxisCORE uses an internal 64 sample buffer). How do we process events in those pipelines and allow them to talk to each other without interfering with each other? Now add in the principle of edit everything live where we want to be able to insert new components, live compile code, or load resources, all without pausing or glitching.

Solving this problem was probably my initial reason for developing PraxisCORE. There’s some great software out there for working with audio or with graphics / video. However, there’s not a lot that I consider works well with both at the same time. For example, I think Processing is a great project - the live video coding API in PraxisCORE is based on it for a reason! But as a system for working with multiple media it is frustratingly lacking. This is not due to a lack of libraries for audio, etc. but because the underlying architecture is fundamentally tied to a single frame-rate based model.

What’s wrong with synchronization? … Everything!

Working with different media in this way is analogous to working with threads. In fact, in most cases this is exactly what we’re doing. Now a common way of handling communication between threads in a Java program is to use a synchronized block, or other form of locking. Unfortunately, these are terrible ways of dealing with this problem.

Time waits for nothing

There’s a great article by Ross Bencina (author of AudioMulch) called Real-time audio programming 101: time waits for nothing. It discusses in some detail the reason not to use mutexes and other common threading constructs when programming real-time audio. I’d consider it a must-read for anyone doing audio coding, and useful for anyone working with real-time requirements.

Remember your media thread is for processing media! You need to be aware of all the code that is running in that thread, and the maximum potential execution time of that code, to ensure your data is processed in time. If you start adding in locks, then besides the overhead of synchronization and putting your code at the mercy of the scheduler, you add in the possibility of contention with other code that is now effectively running in your real-time thread but might not be able to meet your real-time deadlines.

Optimization

There’s another problem with locks, and that is working out how coarse-grained they should be – how much code they should cover. You might expect that for best performance you’d want to keep the lock as fine as possible, only covering the minimal required code in an individual component. Besides being a bad idea as mentioned above, it also inhibits a more important performance optimization that happens in the PraxisCORE code. Audio, video and data pipelines switch off processing of sections of the graph where they can prove the output is not required. To achieve this, they need to be sure that changes can only happen at a particular point of each processing cycle. However, to achieve this using mutexes would massively increase the chances of contention.

Atomicity

Another problem with synchronization is one of misapprehension, but one I’ve seen on multiple occasions. Imagine for a moment you have an audio sample player type, and on that type is a synchronized play() method. From your control thread (maybe Processing’s draw() method) you call play, and the sample plays fine and all is well. Now imagine you decide to play 4 samples together, so you call play() 4 times in succession and all is well .. actually, no it isn’t, because there’s no guarantee that those 4 samples will play together. This is another issue with using locks – how can the user ensure that a series of events happen atomically?

The PraxisCORE architecture

One (probably the) way to deal with the issues above is to pass events into your media process using a non-blocking queue or ring-buffer. I’ve written a variety of code in the past that used variations on these methods, and I’ve used a variety of other “non-blocking” concepts (such as Futures) for dealing with resource loading, etc. However, mixing different techniques for different requirements can be problematic! PraxisCORE began life as an experiment to build an architecture based entirely around a single, uniform message-passing model. It is inspired by the actor model, with some notable divergences.

A forest not a tree

Components (actors) in PraxisCORE are arranged in trees. Each component has an address in a familiar slash-delimited format (eg. /audio/filter ). There is no single root - / has no meaning. Instead, the first element of the address refers to the root component, of which there can be many - a hub of roots creating a forest of actors. Roots generally, but not always, encompass a thread of execution.

Diverging from the typical actor model, components do not maintain their own queue for incoming messages. Mailbox functionality is handled by each root, with external messages being delivered through a single lock-free queue, putting the root component in charge of all scheduling. Messages also have a time stamp. Each root maintains a clock relative to an overall hub clock, ensuring messages are dispatched at the correct time.

Each component has zero or more controls, which act as end points for messages and are addressed in a form that echoes function calls (eg. /audio/filter.frequency). Controls may wrap simple properties and actions, or complex functions that set off a chain of further messages. PraxisCORE adheres to a principle of no shared state between components, and control call communication uses a simple immutable type system. Even the code of each component is backed by a control - source code received as data to a component sets off a chain of messages that compile the code and inject the new behaviour atomically.

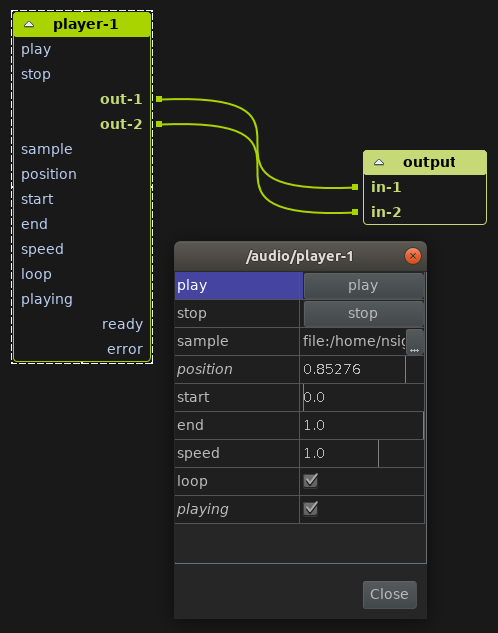

As well as controls, components can have input and output ports, sometimes reflecting the same data. Ports provide a lightweight way for sibling components to communicate, and it is port connections that are reflected in the visual dataflow editor. Port communication itself is synchronous, although components can create or delay onward port messages, or use them to trigger asynchronous control calls. Port communication uses the same immutable type system, but extends this with the ability to pass mutable data such as audio buffers and video frames. This provides the ability to process real-time data in a lightweight and lock-free way across a series of components, while maintaining the strong encapsulation of the actor model.

Here you can see an example of an audio:player component from within the PraxisLIVE editor. Ports can be seen on the graph node itself, and controls within the open editor dialog. Note the correlation between them. Manipulating values within the editor dialog sends control messages to the component. Note also the ready and error ports - because loading a sample file is not real-time safe, the sample port triggers an asynchronous control message, with port messaging continuing on response.

At your service

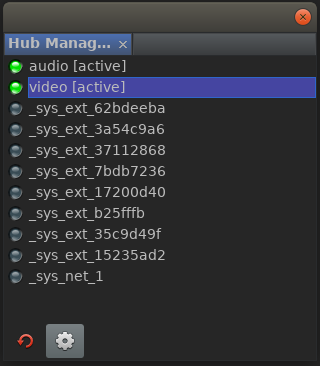

Alongside an unlimited number of user root components, there are various system-defined roots. Here you can see the Hub Manager inside the PraxisLIVE IDE with the system roots toggle active. Some of these roots provide services such as the compiler or resource loader. The runtime is modularized and decoupled, and a service discovery mechanism is used by components to find the addresses of services they require. Another of these system roots might be the PraxisLIVE IDE itself. The IDE can only communicate with the runtime via message passing, and other components have no knowledge of the IDE, making it easy to disconnect it, or swap in another editor that represents the underlying model in a different way.

Distributed root hubs

A key advantage of this architecture is its ability to work transparently with roots running in separate processes, literally at the flick of a switch. This makes it possible to edit code and dataflow across multiple machines. It also allows a project to run across multiple local processes, perhaps to improve real-time performance by mitigating garbage collection effects across pipelines. Or to improve resilience by automatically restarting a root in case of failure.

In a Pcl

While it is perfectly possible to control the PraxisCORE system from Java code using callbacks, in a continuation passing style, the recommended way to interact with the system is via the PraxisLIVE IDE. This provides live visual editing of the actor graph, as well as strong introspection facilities. And it supports the editing of code fragments stored in controls on components, with full syntax highlighting and completion (based on top of the Apache NetBeans IDE).

PraxisCORE also has a simple text based command language. The syntax of this is loosely based on Tcl - and if that is pronounced tickle then Pcl must be Pickle! It is the language used inside the Terminal component in the PraxisLIVE IDE, and also the syntax of all the files used in projects.

Two common commands, with symbolic aliases, are @ (at) and ~ (connect). @ takes a component address, an optional component type (used to construct a new component) and a script (that will be run within the context of the address, allowing nested hierarchies. This simple language hides the complexity of working within the PraxisCORE message-passing system, the interpreter automatically handling the sending and receiving of messages.

This is a simple script used to create a simple graph identical to the Hello World example in the examples download – it is similar to the the contents of the video.pxr file from the graph editor. There are actually 5 different roots (threads) involved in the execution of this script, potentially split across up to 3 processes!

@ /video root:video {

.width 400

.height 300

.fps 20

@ ./noise video:source:noise {}

@ ./image video:still {

.image [file "resources/hello world.png"]

}

@ ./window video:output {

.title "Hello World!"

}

~ ./noise!out ./image!in

~ ./image!out ./window!in

}

/video.start

In practice in Praxis

Praxis (from Ancient Greek: πρᾶξις, translit. praxis) is the process by which a theory, lesson, or skill is enacted, embodied, or realized. (Wikipedia)

What began life as an experiment into a message-passing actor system for real-time use has now matured into a robust and resilient runtime. The initial complexity of building a general purpose system in this way has paid dividends over the years in the ease of working with almost any library on the JVM. And with lock-free messaging and strong encapsulation it has proven to be an ideal and natural architecture for supporting real-time hot code reloading in Java.

Come get involved in the next exciting steps for PraxisCORE, bringing the best aspects of Erlang, Smalltalk and Extempore into the Java world.

This post is based on a much earlier 2012 blog post at The Influence of the Actor Model, updated (and abridged, honestly!) with snippets from my ICLC conference paper on PraxisLIVE and other more recent aspects of PraxisCORE.